Trust by IV Drip: A Strategy That Outlives Silence

Any good service, beyond faithfully delivering on the promises stated in its description, must contain a component of talent. Simply fulfilling contractual obligations is the baseline. That’s how it should be. Which is why statements like “We provide high-quality/professional services” have always puzzled me. Read closely and you’ll see: this isn’t competing with the strongest players; it’s competing with those who don’t know how to work, who lack experience and overpromise, or who have issues with basic integrity. Real results appear only where there is talent—or an overcompensation for its absence, embodied in hard, sustained work.

I propose we start on that level at once: not talking about “quality” and “professionalism” (those are table stakes), but focusing attention on strengths—what many call talent. We all know companies hunt for talent defined by the specifics of their tasks. In your view, what core abilities are required to deliver information to people who (a) are not initially interested in receiving it, (b) are overloaded by incoming noise, and (c) exhibit a generally high level of distrust toward any intrusion into their private space? I’m sure several answers have already flashed through your mind. Possessing all of them at once is a rare gift, granted to a few. We weren’t among them.

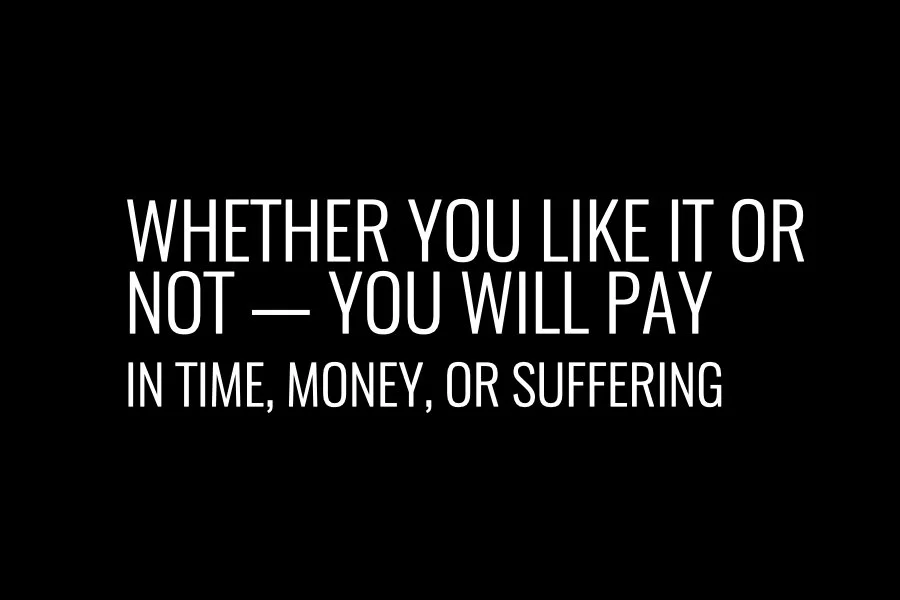

On our path, nothing came easy. You know this as well: business isn’t about ease. Those who win are the ones who can overcome difficulties and stay the course. Over time, the struggle becomes normal; discipline, patience, and resolve harden. At some point you simply have more of these than others—not because of innate talent, but because you devoted more time to the work than someone else did.

You’ve met people who have been immersed in a single topic for years and therefore know more about it than others. Of course. The simplest example is scientists: if someone has studied physics daily for twenty years, it’s very likely they understand their subject more deeply than you do (assuming you didn’t walk the same road). But if you have a talent for physics, you can traverse that twenty-year route faster—and prove it in the demonstration. That’s how talent manifests: in the moment of proof.

For the last twenty years we have devoted ourselves to a single question: how to use remote activation of a recipient’s attention to place the right information in their mind—information that leads to the expected reaction. It’s not a unique vector; many work on this, write academic papers and books, and build training programs. But when the time comes to demonstrate, most retreat into a defensive crouch, leaning on their credentials and lofty rhetoric, insisting they don’t owe anyone proof. How, then, are we to know that you—yes, you specifically—are capable of what warrants being called a professional?

“Look at my sales,” you might object. “They prove everything.” Sales demonstrate the ability to close deals—a valuable skill in its own right. But if you sit at a cinema ticket window, you can hardly claim the film’s box office success is thanks to you—“look how many tickets I sell every day.” The metaphor is clear: sales departments—whether in-house or as exclusive contractors—sit atop an inbound stream of demand. That lets you show good numbers, but it doesn’t justify the claim that you can implant ideas into UHNWI minds by activating their attention. And the budgets you wield… with that level of spend, having no sales at all would be a disgrace.

If you’re that talented, demonstrate it: select a group of UHNWI and achieve the expected outcome using only time and your professional skill—without a corporate daddy and his fat checkbook. That will be proof. If you truly possess the gift of persuasion, charisma, and the full set of required qualities, you’ll do it quickly. We’ll envy you—in a good way. We don’t have those traits, nor do we have a fat checkbook to carpet-bomb the market with information. What we do have is patience—and the understanding that you can “reach” any person on the planet if you invest enough effort and time. And it’s crucial to remember: people arrive at the same decision at different times; some need more information, others less.

Let’s posit a “point X” at which each person has enough data to decide. If the offer is new, one must first acquire evaluation tools and only then the data themselves. Yet everyone’s experience differs: at first contact one person rejects, another suspects, a third is intrigued, a fourth even reacts with aggression. That’s the starting line. There will always be those who say “no” immediately. What matters is the size of the audience that remains after the first touch. If no one filters out and not a single question appears after your first message, then the offer is either unclear or so absurd that it draws no response. That’s the worst scenario. In that case, you must rebuild from scratch—and repeat until you provoke at least minimal reaction. This is our strategy—the strategy of those without the “talent for instant persuasion.” It doesn’t shorten the distance in the moment, but over 2–3 years it produces a stable, reproducible result.

By that point, your audience knows who you are and what you offer; the uninterested have been replaced by those still undecided; many questions are resolved; and you’ve learned a great deal about your product—and yourself. Ultimately we reach goals through endurance and discipline: some people fall away, others take their place; the cycle never ends. In your ongoing communication list remain only those who haven’t yet said “no.” That is your potential audience—its moment simply hasn’t arrived. Everything depends on where a person was in their own cycle when you began to engage.

For example, a typical ownership horizon for a private jet (purchased new, absent idiosyncratic usage or force majeure) is 6–8 years. If you touch a UHNWI right after a fresh purchase (we’ve heard this more than once: “I just bought”), the next window for a deal is years away. That’s no reason to strike the person from your communications. On the contrary, if they don’t object, you should unobtrusively and regularly supply useful information about their aircraft model throughout that period—so that when the next decision point arrives, they have a real alternative in choosing a seller. The seller who closed the last deal will almost certainly “forget” the client for most of the cycle—at best, there’ll be an occasional generic mailing and corporate invites. That’s your chance. The same logic applies to any asset: everything has a typical ownership horizon. The lives of billionaires do not stand still. The fact that you didn’t receive a response today doesn’t mean you won’t receive one tomorrow or a year from now. But we know exactly who won’t receive a response: those who never try—or who decide they are “entitled” to one.

This is not blind stubbornness. It’s a highly adaptive model that constantly searches for gaps in the armor, creates events that activate attention, and guides the process toward the goal with delicacy and precision. Many simply aren’t used to cycles longer than a year—and they lose faith. But when you’ve been inside the process for nearly twenty years (and many of your recipients have as well), you see and know these cycles are real. The decisive factors are not only liquidity windows, approaching ownership horizons, family circumstances, and other triggers, but also how much of your information has been integrated into UHNWI consciousness by the time one of those events arrives. Now imagine you are working, simultaneously and regularly, with thousands of UHNWI from a standing start: step by step you become recognizable, and once sufficient credit of trust has accumulated across a large audience, your odds of succeeding in subsequent buy/sell events rise sharply. Trust is infused drop by drop, not poured in a single surge; an inseparable component of trust is time.

The earlier you begin, the sooner you approach the real goal—being recognizable within the UHNWI circle. A big brand or grand project does not grant trust in advance; at best, it lets you enter on the second or third rung. The rest is luck: if your information collides with someone at the exact end of a cycle, you may see a quick win. But luck is no basis for strategy.

So, we didn’t have the inborn talent to win people over at first word. That’s why we had to work longer and harder. As a result, we’ve accumulated enough experience and understanding to deliver messages into the minds and consciousness of those who are hard to reach. If you need an instant result, we’re not your choice. If you want a predictable outcome as the consequence of a well-calibrated strategy, we’ll be glad to work with you.